I talk about horsekids a lot. They’re the people who live for the horses, whose soulmates are equine and their human partners either accept it or find themselves out on the road. Horsekids are a distinct subspecies of human, and they take a very dim view of any misrepresentation of their beloved horses.

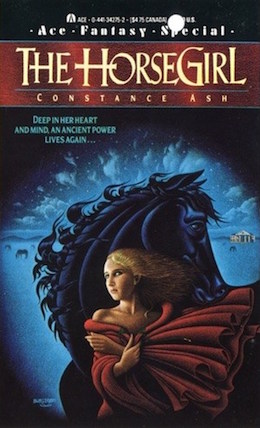

I’ve known Constance Ash for many years, and I know her as a true horsekid. She not only walks the walk, she’s written a fantasy novel, first of a trilogy, titled The Horsegirl—and it’s exactly what it says on the tin. It’s also, for a book published in 1988, remarkably fresh and timely for 2019.

The Horsegirl is Glennys, raised by dour frontier evangelicals in a world ruled by the horse-riding “Aristos.” Glennys’ mother once served the lord of the county, Baron Fulk, but left him to marry an Alaminite cultist. It’s a difficult life in a hardscrabble town, where men rule and women are property, and daughters have little value.

Alaminite doctrine demonizes horses, but Glennys dreams of them, until one day one of Baron’s stallions escapes and bolts onto her parents’ farm.

She discovers that she can communicate with him, which only strengthens the dreams and the yearning—even when the price is to be shamed and beaten by the bishop of the town kirk.

This does not turn out the way the bishop intended. Far from being cowed or suppressed, Glennys finds her true calling. The Baron has recognized Glennys for what she is: a Horsegirl, one of an ancient line of women who can communicate with and telepathically control horses. He negotiates with her mother to take her on as the apprentice to his Stablemaster, with the expectation that she will take over the position when the Stablemaster retires.

It’s a complicated situation, with Alaminite rebels attacking horses and the men who ride and care for them, war and intrigue in the larger world and family conflict on the frontier, Glennys’ parents’ marital problems that end in her supposed father’s being conscripted into the royal army, and Glennys’ own education in the arts of horsemanship. There’s an undercurrent of sexual passion—it’s too raw and inarticulate for romance, and the outcome of Glennys’ lifelong attraction to the Baron is catastrophic for all involved.

The novel is sort of proto-Weird West in its setting and ambience, but with a flavor of the British Empire: as if nineteenth-century Utah had been taken over by the Raj. Although the cover copy makes it seem like a conventional preindustrial secondary-world fantasy, it’s actually set in a world that’s shifting over from swords and cavalry to gunpowder and muskets. Baron Fulk, breeder of war horses, sees his livelihood literally shot down within a few years, and the younger generation is all about the guns and the explosions.

Glennys finds herself in a peculiar position. She’s a Stallion Queen, which in the days of the horse nomads would have been a very big thing, but now it adds up to not much more than a slightly shameful and rapidly obsolescing collection of talents and abilities. She can control horses, but they can also control her, which is dangerous for both sides.

I found the novel unexpectedly dark, almost unbearably so at times, but I could not stop reading. It’s not a happy story and it’s not at all warm and fuzzy about any of the animals in it, including the horses. Especially the horses.

The horses are so real. So are Glennys’ feelings about them. They do not think like humans, and her bond with them is all about their instincts and imperatives, their minds and bodies, their perceptions of the world.

She uses them, sometimes brutally. This is not a gentle world. Animals are not pets or life partners. They’re food, transport, income.

At the same time, an animal who gives good service gets respect in return. If it suffers or dies, it’s mourned. When it’s a horse, especially a war stallion, it can be something more; something numinous.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

This is true of the first stallion Glennys meets—the beautiful chestnut racer—and of other horses she comes to know, but most of all the Baron’s own charger: the great black horse called Deadly. Glennys’ bond with him is deep, and it goes both ways. In his mind, she belongs to him.

There’s nothing soft about it. He goes away for years to the war, and she wastes no time pining after him. She’s busy learning, growing, training. When he finally does come back, battered but unbowed, she is still a part of him and he of her, but she has found a new obsession: She falls in love with a human man, with devastating consequences.

However, like many a horsekid, she finds her way back to the horses. We don’t know at the end of the novel what will come of it, but we do know that she’s still a Horsegirl. There’s no altering that.

It take a horsekid to write a book like this. To be so unflinching about the ways humans use and abuse their horses, and to build a world around the minutiae of riding, training, breeding, horsekeeping.

Glennys studies all the facets of horses and riding. She learns to be a groom, a stablehand, a breeder, a master of horse. Her preoccupations are not only with the fun stuff, galloping bareback across the Badlands and learning to hang off a horse’s neck by a toe and snatch a knife from the ground, but also the hard and finicky work of calculating feed rations, ordering supplies, maintaining pastures, facing a collapse in the horse market and recognizing that if the horses don’t sell, they have to go for meat and leather. If a horse is mortally injured, he’s put down; if there’s sickness among the livestock, the stables have to go into quarantine, and it’s accepted that some or all of the stock will die.

As hyper-real as The Horsegirl can be, it’s hardly a nonstop ordeal of grimdark horror. Glennys finds joy in a good part of her life. After the great reversal, when she’s pulled away from it all, she comes to realize who and what she truly is, and finds her way back to the horses.

This is high up on my shortlist of books that get the horse-stuff right. The details of training, handling, veterinary care, feeding, and maintenance are spot on. So are the glimpses of the mind and psyche of the horse, even the way in which Glennys can become one. In our world, we can’t necessarily go that deep, but some of us come close.

Horses come first with Glennys, always, except for the brief romantic interlude; but even there, they’re still very much a part of her. She can’t imagine life without them. That’s how it is, if you’re a horsekid.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.